Telling you all about it will motivate me to do these posts as well.

Please please give me feedback in the comments section. I would love to hear from my followers about what you want to read about.

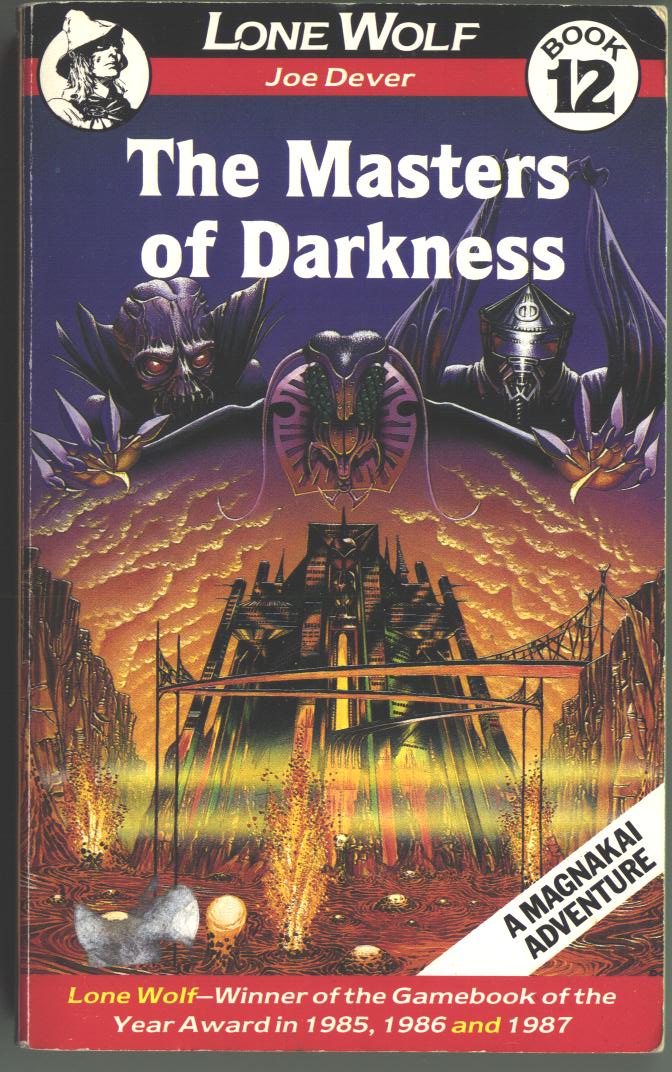

You Adventure ends here

I intend to finish this series off with a post about how death paragraphs reveal information, a few of my personal favourite failures and then a conclusion. So three more posts of this.

Codewords

When shoud we use them?

What should they be?

Do we have any neat tricks we can do with codewords? (I'm looking at you, Crimson Tide)

Handling stupid decisions in gamebooks

What constitutes a stupid decision, why you should offer them and what the consequences of them should be.

Wounds and healing

How deadly should your wounds be? Should food and water provide healing or should it be a long hard process to recover? How deadly should combat be?

Mass battles in gamebooks

What systems have been used and how should they be handled?

Gods and priests in gamebooks

What are your gods like? What role do priests play in your world? How are they different from sorcerers with a sense of morality?

Money and shopping in gamebooks

How important should it be? What can be bought and sold in gamebooks? What other things can money buy? How many currencies should you have? Should you have it so they hero never has enough money?

Food and water in gamebooks

Should it heal?

Should hunger and thirst cause damage?

Generic meals or named food?

Revealed information in gamebooks

What are the good points and bad points of showing a reader that something different will happen if they have an item or codeword?

How are programs which don't reveal this information play differently?

Should gamebooks tell you how you feel?

Description or emotions? How does it affect your character? How does it affect the game?

Skills and abilities in gamebooks

What skills and abilities add to a gamebook. What they take away. How to make sure you have a balance of character creation choices vs choices in the book.

The level of magic in gamebooks

What magic items are available? Can you buy them like food or are they rare and well hidden? How many magical monsters or magic wielders do you come across in the book? Does your level of magic fit the leevl of the rest of the book? What kind of spell systems could you have?

Items in gamebooks

How items can be used. How they shouldn't be used. When do you have too many items? Would an encumbrance system help?

Morality in gamebooks

What does having a sense of morality in gamebooks add to the gamebook? How can you enforce that morality?

What writing microadventures taught me

It's amazing what a 25 paragraph gamebook can do.

Amateur gamebooks, gamebook programs and games that read like gamebooks

A list of wonderful things I have found online.

So there you go. Please leave feedback about the blog as a comment so far and tell your friends!

Something to look out for.

Fighting Fantazine issue 5 will be out soon. Don't miss it!

And finally...

I like cats. I also found this blog about a cat, which has 180 followers. So here is a picture of a cute cat.

If you like cats and H.P. Lovecraft, I recommend The Cats of Ulthar, a short story by Lovecraft which I enjoyed.